Once in America, Abraham and Ella Land had two more sons and three daughters. In an incident typical for immigrants to America, they acquired the name of Land and Avram's name was Americanized to Abraham.

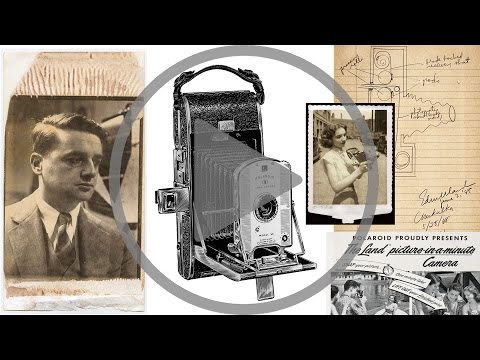

Such surveillance, by giving incontrovertible physical evidence ofĪs refugees from the ever-tightening persecution of Jews during the reign of Russian Tsar Alexander III (1881–94), Land's grandfather Avram Salomonovitch, his grandmother Ella, Land's father Harry, and uncles Sam and Louis, sailed from Odessa and landed at Castle Garden in New York City. The crisis of the 1950s, when thermonuclear weapons were succeeding nuclear ones and an open United States confronted a closed Soviet Union, brought Land into a crucial role of energizing and supervising high-altitude airplane and satellite surveillance from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s. Research on color vision, which he described in lectures at the National Academy of Sciences in 19, brought him into conflict with many in psychology-but eventually led to collaborations with neurophysiologists. He became a vigorous prophet of the efficacy of science-based companies in promoting innovation and providing all their workers a rewarding life on the job. But as a pioneer of the science-based company from the early 1930s, he frequently formed alliances with big firms, such as Eastman Kodak, to manufacture components of the systems. His desire for autonomy and the challenges of reliably manufacturing his inventions reinforced his determination not to be absorbed by large corporations with large research budgets. The polarizers in turn led him into work on the Vectograph process of three-dimensional photography, which found its first important application in reconnaissance during World War II. Those innovations had a prehistory: twenty years' work on the first plastic-sheet light polarizers, the great invention of his youth. Land's attitudes from boyhood were those of a physicist, but he is best known as the inventor and re-inventor of instant photography from the mid-1940s to the early 1980s. He told a press interviewer, "My whole life has been spent trying to teach people that intense concentration for hour after hour can bring out in people resources they didn't know they had." The watchword was: "If anything is worth doing, it's worth doing to excess." This principle applied also to behavior in the laboratory.

Despite a soft voice and frequent use of half-sentences, Land was able to convert interior monologues into dramatic public presentations. Less than six feet tall, Land had intense eyes and a shock of black hair that riveted attention on him. Less evident was a remark-able ability to keep both work and people in compartments. Besides energy, the dominant impressions Land created were artistic sensibility, a sense of drama, delight in experiment, relentless optimism. Until late in his life, he took pleasure in leaping up stairs two at a time. Wiesner was referring to the extraordinary versatility of Land's mind and conversation, which enabled him to concentrate intensely on solutions to problems, and to charm and win over the talented people to tackle them. As the group talked about Land's character, Jerome Wiesner ex-claimed, "Din never had an ordinary reaction to anything!" Speakers would have to encompass topics ranging from color vision to business innovation, from military intelligence to patronage of architecture. Land was not just a scientist-industrialist. Swiftly, they decided on a title, ''Light and Life." The agenda, however, was more difficult.

LESS THAN TWO WEEKS after Edwin Land's death in 1991, members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (and the author) met to plan a day-long memorial conference.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)